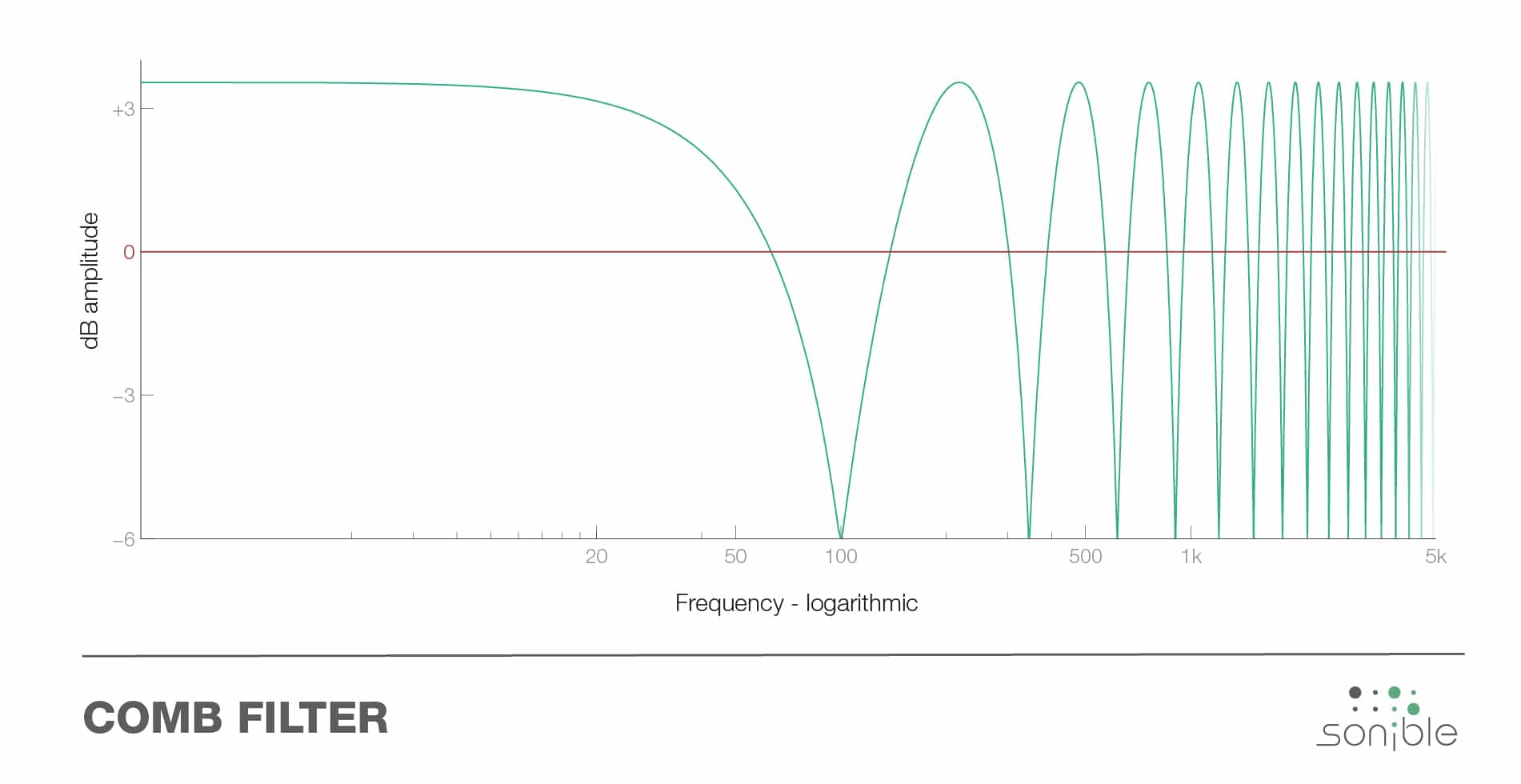

Comb filtering is produced when certain frequencies are either amplified or attenuated by the superposition of a delayed version of the original audio signal onto itself. The frequency response curve of a comb filter consists of a series of regularly spaced notches, giving the appearance of a comb.

This superposition leads to certain cancellations and amplifications in the audio spectrum that in turn produce a metallic sound. Voices sound harsh and sharp due to significant parts of their fundamental frequency range being cancelled out. That phenomenon is called comb filter.

Comb filters become particularly disturbing when they change over time – as can happen when the sound source (e.g. a musician) or the microphone moves during the recording process. As a result, the first reflections are continuously changing and the comb filter in turn migrates across the audio spectrum. This time-varying attenuation and amplification of different frequencies is called “phasing”.

Protip: It is very difficult and sometimes impossible to remove recorded comb filters and phasing effects in later stages of audio production. You should therefore avoid them during the recording process to prevent unsolvable problems during mixing.

The form and strength of the comb filter effect depends on the length of time between the original sound source and its earliest reflections. If the strongest reflections occur less than 2 ms after the original sound, any comb filter characteristic is not very disturbing as at this time only high frequencies are being particularly affected. As the delay/reflection time approaches 10 ms, the cancellations and amplifications of the comb filter move into the fundamental tone range and the comb filter effect becomes more audible and problematic.

If the first reflections arrive later than 15 ms, the human ear manages to separate the two sound events (direct sound and its reflection). The comb filter effect becomes weaker and eventually disappears completely when the time delay between the two sound events is long enough.

It is fairly easy to calculate position of the comb filter notches for any frequency. Where the attenuation occurs, can help us to figure out where the disturbing reflections are coming from.

The distance of the notches fd is determined by the runtime difference dT between the direct signal and the disturbing reflection, the comb filter produces:

fd = 1/dT (dT = runtime difference)

The first notch f1 is located at 0.5 fd, for all following notches you need to add fd. That means, when the delayed signal arrives 2 ms later, the first notch of the filter lies at 500 Hz, the second at 1,5 kHz, the third at 2,5 kHz and so on…

fd = 1 / 0.002 (2 ms) => fd = 500 Hz

f1 = 250 Hz | f2 = 750 Hz | f3 = 1250 Hz | …

Sound travels with 340 meters per second. So 2 ms delay means 70 cm distance and 15 ms delay 5 meters. Therefor, if the distance of the microphone to a wall for example ranges between 0,7 and 5 meters, it is likely to produce unwanted comb filter effects.

Undesirable comb filter effects can thus be best avoided during the recording session by keeping the time difference between the direct sound and its first reflections either as short or as long as possible. In order to visualize the effect let’s convert the difference in time into distance; nine to twelve ms equals approximately three to four meters.

In order to avoid reflections as effectively as possible, walls or other surfaces close to the microphone or the instrument should be acoustically dampened (e.g. with acoustic foam). Another possibility is to change the position of the singer or instrument and the microphone so that as few reflections as possible fall into the critical time range of ten to fifteen ms. This can be achieved by either moving the audio source as close (< 3 metres) as possible to the reflecting surface or as far away (> 5 metres) from it as possible.