For 22 years now, Tom Wiggans, FOH engineer and production manager, has been touring with bands all over the world. Recently the Brit toured with Bloc Party as well as Bombay Bicycle Club in the U.S. and Amy Macdonald in Europe. When he talks about his impressive career, Garbage, Natalie Imbruglia, Red Hot Chili Peppers, the Cranberries, UB40 and Travis pop up. With such an amazing roster of artists, a person might be tempted to boast a little. But there is no boasting with Tom, only interesting insights and a lot of expertise.

Tom’s path to becoming a successful FOH engineer wasn’t exactly straightforward – the side roads seemed much more appealing to him. As a teenager, Tom dabbled in playing the guitar but his enthusiasms for the instrument didn’t last: “I never really progressed beyond making weird noises.” What actually captured his interest were effect pedals and other audio devices. So, he decided to study electronic engineering. As it turned out, it wasn’t quite what he expected: “I hated electronic engineering. I was interested in audio applications and such stuff. None of my lecturers had any interest in that.” Still, attending university was ultimately the right decision: “I got heavily involved in the technical department of the student union – a kind of voluntary student-run sound and lighting company – much to the detriment of my degree. It took me four years to complete a three-year course.”

Whilst working for the student union, Tom made a few contacts in a company called SSE Audio group that provided services to the live events industry. He landed a job there and was assigned the most basic tasks at first: “I occasionally worked there for 3.75 £ an hour, sweeping floors, building speaker boxes and stuff like that. Then one day, because I was a go-around, they started letting me be an extra person at the shows they did. It was a great opportunity to learn all the equipment. After that, they were testing me to go out to festivals and later on tours.”

By 1999 he was assistant tech for Garbage, Natalie Imbruglia and the Red Hot Chili Peppers. “I started off being a monitor technician but always wanted to mix bands. When you make a living being a technician, you are the one who looks after the guy who is mixing. Looking back, it was a great step because I got to stand behind people who were really good and I learned a lot. Even when they made mistakes it taught me something – it’s all knowledge.”

UB40 was the first band he worked for as an FOH engineer, thanks to one of the directors of SSE who had faith in Tom’s skills. “Because of UB40’s relationship with him, they weren’t worried about who I had mixed in the past. They said: ‘If he says you can do it, that’s good enough for us.’ Whereas prior to that, I couldn’t get gigs because, although I had lots of experience in being a technician, I had no mixing experience.” His work with UB40 lasted for 5 years, after which many bands followed.

Regarding his role when he’s touring with bands Tom says: “I’m obviously there to make them sound good but also to be objective and to make everyone happy.” The latter is especially tough to do, considering how many people are involved in a show. From gear to social skills – there are several things that Tom deems to be crucial in making it happen. “While having gear and equipment that you’re familiar with helps you mix the show, the real thing is knowing what’s supposed to be happening and who’s playing what and how. You need to know the songs and the arrangements fairly well. That knowledge is more important than anything else.”

To understand how the songs are supposed to sound, he generally refers to the band’s recorded studio productions but first makes sure that those arrangements are still something they are happy with. “I am not afraid to discuss this with the band because quite often the current arrangement will deliberately differ from how it is on the record – especially when there has been a bit of time between the tour and the recording.”

When Tom does gigs he takes a lot of notes and tries to get as much feedback as possible from the band afterwards. “Something I learned and did right from the start is recording my desk mix and giving it to the band after the gig. After I did my first show mixing UB40 and gave them the recording, I got a proper telling-off about a number of things.” Instead of making a fuss, he went and got his notebook and wrote down all their comments. The next evening, after hearing the recording of the second show, they realized that Tom had addressed and listened to all their comments. “That builds a trust that can put you on a level footing with other factors like management or other people’s opinions.”

“During a gig, a FOH engineer is the most consistent observer of the show from an audience’s perspective”, as Tom puts it. In 22 years of touring he has been a part of a lot of amazing shows and for him, this isn’t necessarily so much to do with the sound. As Tom explains: “I think the most memorable shows have to do with the audience’s reaction. It’s the vibe in the environment.” Therefore, his priorities are very clear when it comes to vibe vs. technical immaculateness. “It’s my challenge to work out a way that fixes, for example, a few issues with spill but I’d rather have the vibe than stifle everything. As an FOH engineer you are basically there so that the band doesn’t have to worry about technical stuff. They can just go on playing their show and be confident that they’ve got someone who’s representing them out front, who gets what they’re about and is doing their best for them.”

Tom’s biggest challenge is being in competition with himself: “During a show it’s rare that I’m actually enjoying it. Normally, I’m so focused about what’s happening right now and reacting to things that it’s only afterwards when I can relax and be like ‘Yeah, that was actually pretty good.’” He admits that it took him quite a long time to have confidence in making the right decisions. The encouraging words and trust of the artists who hired him finally made him realize that he is actually good at what he does.

When listening to Tom’s anecdotes about chaotic gigs, time-critical situations and effective collaborations, it becomes obvious that communication and trust go hand in hand. Both seem to make Tom’s work a lot easier – well, that and the right gear.

“Always make sure that the source is correct. When you get the right source, you have less processing to do,” advises Tom. For him, discovering the use of different microphones was a big step. “I use a lot of DPA microphones but not just them. I am very specific about using the correct microphone.”

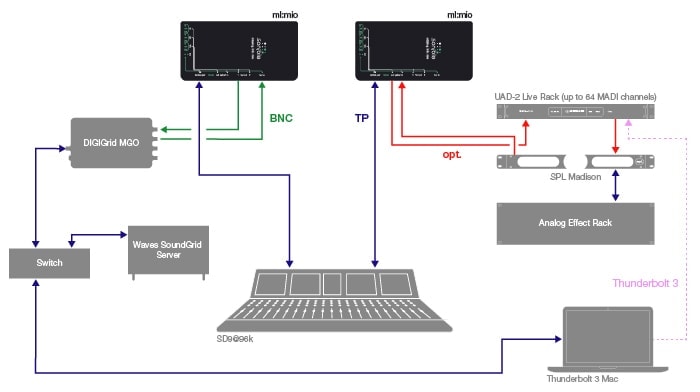

That’s why on tour his mic package goes wherever he goes, along with a Waves MultiRack and, if he has the luxury, the SD9 mixing console by DiGiCo. “The SD9 suits my workflow. It is small and with it I am not the guy taking up all the space in the FOH tower at festivals.” Tom says that the only downside of the SD9 is its connectivity. “I use it with an SD rack by an optical link which means there’s three MADI ports on it, two are twisted pair, one is BNC. So, previously I always ran out of I/Os. I always multitrack a show so that I can listen back and tweak things.” Recently he added the MADI media converter, router and splitter ml:mio by sonible to his equipment. “With the ml:mio all of a sudden I can use two twisted pair ports. I can turn the DiGiCo-proprietary formats which were pretty much of no use to anyone into fully functioning MADI ports – it’s fantastic.”

The reason he likes to connect via MADI is simple: Tom no longer then has to worry about vendor dependent and constantly changing protocols with the AES approved standard. “I tried the ml:mio and I was like ‘what an incredible little box!’. Now, when I get a standard SD9 and it doesn’t have a Waves port, I route my first twisted-pair port via one ml:mio to optical MADI and into the live rack; the second one will go twisted-pair into BNC via another ml:mio and into my DiGiCo MGO which will go on a network and run the Waves stuff. ml:mio gives me so many options.”

One might assume that being an FOH engineer in a small club is far easier than in an arena with a capacity of 15,000 people or more. But Tom, having done both for a long time now, says: “When you are starting to mix bands front house then you’re probably in a small venue that has really poor acoustics, especially when empty. The gear and microphones you are using might not be that good and chances are that the band you’re mixing may not be so good. So, the thing to remember is that it gets easier. In my opinion, mixing in an arena is far easier in terms of acoustics than in a club. The PA systems are better and the spaces are much better too.”